Понижает тонус симпатической иннервации на сосуды

(нейротропные гипотензивные средства)

Высшие центры симпатической нервной системы расположены в гипоталамусе. Отсюда возбуждение передается к центру симпатической нервной системы, расположенному в ростровентролатеральной области продолговатого мозга (RVLM – rostro-ventrolateral medulla), традиционно называемому сосудодвигательным центром. От этого центра импульсы передаются к симпатическим центрам спинного мозга и далее по симпатической иннервации к сердцу и кровеносным сосудам. Активация этого центра ведет к увеличению частоты и силы сокращений сердца (увеличение сердечного выброса) и к повышению тонуса кровеносных сосудов – повышается артериальное давление.

Снизить артериальное давление можно путем угнетения центров симпатической нервной системы или путем блокады симпатической иннервации. В соответствии с этим нейротропные гипотензивные средства делят на средства центрального и периферического действия.

К гипотензивным средствам центрального действия относят кло-нидин, моксонидин, гуанфацин, метилдопу.

Клонидин (клофелин, гемитон) – а2-адреномиметик, стимулирует а2А-адренорецепторы в центре барорецепторного рефлекса в продолговатом мозге (ядра солитарного тракта). При этом возбуждаются центры вагуса (nucleus ambiguus) и тормозные нейроны, которые оказывают угнетающее влияние на RVLM (сосудодвигательный центр). Кроме того, угнетающее влияние клонидина на RVLM связано с тем, что клонидин стимулирует I1-рецеттгоры (имидазолиновые рецепторы).

В результате увеличивается тормозное влияние вагуса на сердце и снижается стимулирующее влияние симпатической иннервации на сердце и сосуды. Вследствие этого снижается сердечный выброс и тонус кровеносных сосудов (артериальных и венозных) – снижается артериальное давление.

Отчасти гипотензивное действие клонидина связано с активацией пресинаптических а2-адренорецепторов на окончаниях симпатических адренергических волокон – уменьшается высвобождение норадреналина.

В более высоких дозах клонидин стимулирует внесинаптические а2B-адренорецепторы гладких мышц кровеносных сосудов (рис. 45) и при быстром внутривенном введении может вызывать кратковременное сужение сосудов и повышение артериального давления (поэтому внутривенно клонидин вводят медленно, в течение 5-7 мин).

В связи с активацией а2-адренорецепторов ЦНС клонидин оказывает выраженное седативное действие, потенцирует действие этанола, проявляет анальгетические свойства.

Клонидин – высокоактивное гипотензивное средство (терапевтическая доза при назначении внутрь 0,000075 г); действует около 12 ч. Однако при систематическом применении может вызывать субъективно неприятный седативный эффект (рассеянность мыслей, невозможность сосредоточиться), депрессию, снижение толерантности к алкоголю, брадикардию, сухость глаз, ксеростомию (сухость во рту), констипацию, импотенцию. При резком прекращении приемов препарата развивается выраженный синдром отмены: через 18-25 ч артериальное давление повышается, возможен гипертензивный криз. β-Aдpeнoблoκaтopы усиливают синдром отмены клонидина, поэтому совместно эти препараты не назначают.

Применяют клонидин в основном для быстрого снижения артериального давления при гипертензивных кризах. В этом случае клонидин вводят внутривенно в течение 5-7 мин; при быстром введении возможно повышение артериального давления из-за стимуляции а2-адренорецепторов сосудов.

Растворы клонидина в виде глазных капель используют при лечении глаукомы (уменьшает продукцию внутриглазной жидкости ).

Моксонидин (цинт) стимулирует в продолговатом мозге имидазолиновые 11-рецепторы и в меньшей степени а2-адренорецепторы. В результате снижается активность сосудодвигательного центра, уменьшается сердечный выброс и тонус кровеносных сосудов -артериальное давление снижается.

Препарат назначают внутрь для систематического лечения артериальной гипертензии 1 раз в сутки. В отличие от клонидина при применении моксонидина менее выражены седативный эффект, сухость во рту, констипация, синдром отмены.

Гуанфацин (эстулик) аналогично клонидину стимулирует центральные а2-адренорецепторы. В отличие от клонидина не влияет на 11-рецепторы. Длительность гипотензивного эффекта около 24 ч. Назначают внутрь для систематического лечения артериальной гипертензии. Синдром отмены выражен меньше, чем у клонидина.

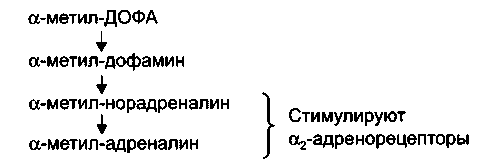

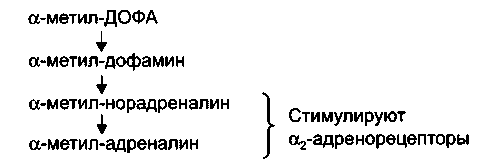

Метилдопа (допегит, альдомет) по химической структуре – а-метил-ДОФА. Препарат назначают внутрь. В организме метилдопа превращается в метилнорадреналин, а затем в метиладрена-лин, которые стимулируют а2-адренорецепторы центра барорецеп-торного рефлекса.

Метаболизм метилдопы

Гипотензивный эффект препарата развивается через 3-4 ч и продолжается около 24 ч.

Побочные эффекты метилдопы: головокружение, седативное действие, депрессия, заложенность носа, брадикардия, сухость во рту, тошнота, констипация, нарушения функции печени, лейкопения, тромбоцитопения. В связи с блокирующим влиянием а-метил-дофамина на дофаминергическую передачу возможны: паркинсонизм, повышенная продукция пролактина, галакторея, аменорея, импотенция (пролактин угнетает продукцию гонадотропных гормонов). При резком прекращении приема препарата синдром отмены проявляется через 48 ч.

Средства, блокирующие периферическую симпатическую иннервацию.

Для снижения артериального давления симпатическая иннервация может быть блокирована на уровне: 1) симпатических ганглиев, 2) окончаний постганглионарных симпатических (адренерги-ческих) волокон, 3) адренорецепторов сердца и кровеносных сосудов. Соответственно применяют ганглиоблокаторы, симпатолитики, ад-реноблокаторы.

Ганглиоблокаторы – гексаметония бензосульфонат (бензо-гексоний), азаметоний (пентамин), триметафан (арфонад) блокируют передачу возбуждения в симпатических ганглиях (блокируют NN-xo-линорецепторы ганглионарных нейронов), блокируют NN -холинорецепторы хромаффинных клеток мозгового вещества надпочечников и уменьшают выделение адреналина и норадреналина. Таким образом, ганглиоблокаторы уменьшают стимулирующее влияние симпатической иннервации и катехоламинов на сердце и кровеносные сосуды. Происходит ослабление сокращений сердца и расширение артериальных и венозных сосудов – артериальное и венозное давление снижается. Одновременно ганглиоблокаторы блокируют парасимпатические ганглии; таким образом устраняют тормозное влияние блуждающих нервов на сердце и обычно вызывают тахикардию.

Для систематического применения ганглиоблокаторы мало пригодны из-за побочных эффектов (выраженная ортостатическая ги-потензия, нарушение аккомодации, сухость во рту, тахикардия; возможны атония кишечника и мочевого пузыря, нарушение половых функций).

Гексаметоний и азаметоний действуют 2,5-3 ч; вводятся внутримышечно или под кожу при гипертензивных кризах. Азаметоний вводят также внутривенно медленно в 20 мл изотонического раствора натрия хлорида при гипертензивном кризе, отеке мозга, легких на фоне повышенного артериального давления, при спазмах периферических сосудов, при кишечной, печеночной или почечной коликах.

Триметафан действует 10-15 мин; вводится в растворах внутривенно капельно для управляемой гипотензии при хирургических операциях.

Симпатолитики- резерпин, гуанетидин (октадин) уменьшают выделение норадреналина из окончаний симпатических волокон и таким образом снижают стимулирующее влияние симпатической иннервации на сердце и сосуды – снижается артериальное и венозное давление. Резерпин снижает содержание норадреналина, дофамина и серотонина в ЦНС, а также содержание адреналина и норадреналина в надпочечниках. Гуанетидин не проникает через гематоэнцефалический барьер и не изменяет содержания ка-техоламинов в надпочечниках.

Оба препарата отличаются длительностью действия: после прекращения систематического приема гипотензивный эффект может сохраняться до 2 нед. Гуанетидин значительно эффективнее резерпина, но из-за выраженных побочных эффектов применяется редко.

В связи с избирательной блокадой симпатической иннервации преобладают влияния парасимпатической нервной системы. Поэтому при применении симпатолитиков возможны: брадикардия, по-выщение секреции НС1 (противопоказаны при язвенной болезни), диарея. Гуанетидин вызывает значительную ортостатическую гипотензию (связана со снижением венозного давления); при применении резерпина ортостатическая гипотензия мало выражена. Резерпин снижает уровень моноаминов в ЦНС, может вызывать седативный эффект, депрессию.

а-Лдреноблокаторы уменьшают сможнотимулирующее влияние симпатической иннервации на кровеносные сосуды (артерии и вены). В связи с расширением сосудов снижается артериальное и венозное давление; сокращения сердца рефлекторно учащаются.

a1-Адреноблокаторы – празозин (минипресс), доксазозин, тера-зозин назначают внутрь для систематического лечения артериальной гипертензии. Празозин действует 10-12 ч, доксазозин и тера-зозин -18-24 ч.

Побочные эффекты a1-адреноблокаторов: головокружение, заложенность носа, умеренная ортостатическая гипотензия, тахикардия, учащенное мочеиспускание.

a1 a2-Адреноблокатор фентоламин применяют при феохромоцитоме перед операцией и во время операции удаления феохромоци-томы, а также в случаях, когда операция невозможна.

β-Адреноблокаторы – одна из наиболее употребительных групп антигипертензивных средств. При систематическом применении вызывают стойкий гипотензивный эффект, препятствуют резким подъемам артериального давления, практически не вызывают ортостатической гипотензии, обладают помимо гипотензивных свойств, антиангинальными и противоаритмическими свойствами.

β -Адреноблокаторы ослабляют и урежают сокращения сердца – систолическое артериальное давление снижается. Одновременно β -адреноблокаторы суживают кровеносные сосуды (блок β2 -адрено-рецепторов). Поэтому при однократном применении р-адреноблока-торов среднее артериальное давление снижается обычно незначительно (при изолированной систолической гипертензии артериальное давление может снизиться и после однократного применения β -адре-ноблокаторов).

Однако если р-адреноблокаторы применяют систематически, то через 1 -2 нед сужение сосудов сменяется их расширением – артериальное давление снижается. Расширение сосудов объясняют тем, что при систематическом применении р-адреноблокаторов в связи с уменьшением сердечного выброса восстанавливается барорецептор-ный депрессорный рефлекс, который при артериальной гипертензии бывает ослаблен. Кроме того, расширению сосудов способствуют уменьшение секреции ренина юкстагломерулярными клетками почек (блок β 1-адренорецепторов), а также блокада пресинаптических β 2-адренорецепторов в окончаниях адренергических волокон и уменьшение вьщеления норадреналина.

Для систематического лечения артериальной гипертензии чаще применяют β 1 -адреноблокаторы длительного действия – атенолол (тенормин; действует около 24 ч), бетаксолол (действует до 36 ч).

Побочные эффекты р-адреноблокаторов: брадикардия, сердечная недостаточность, затруднение атриовентрикулярной проводимости, снижение уровня ЛПВП в плазме крови, повышение тонуса бронхов и периферических сосудов (менее выражено у β 1 -адреноблокаторов), усиление действия гипогликемических средств, снижение физической активности.

a2 β -Адреноблокаторы – лабеталол (трандат), карведилол (дилатренд) уменьшают сердечный выброс (блок р-адренорецепто-ров) и снижают тонус периферических сосудов (блок а-адреноре-цепторов). Препараты применяют внутрь для систематического лечения артериальной гипертензии. Лабеталол, кроме того, вводят внутривенно при гипертензивных кризах.

Карведилол применяют также при хронической сердечной недостаточности .

Источник

.., .., 2002 . 611.839-08 8.11.2001 . .., .. , ; , . () () – . [1]. – . 2. 3. () – 4, 5. 6-8. 2 7 9. () . . . . . . . . b1- b- . , a2- – a2- 10 11. – () . () II 12 13 14. b1- 15; . II. . Ă (). . . . . 16 17, 18. 19, 20. 19-23. . – 24. – 16, 25-28. – b- b1- b2- 29-32. b- 31. – b1- 31. – () 33-36. b- 37-39. b- – т 40 41 42. 42, 43 , . b- 44. b- 45, 46. b1- b- 45 46. b1 b- . b1- b- b- 29, 31. . — т – 47. – . . – т 24. 48-50. 24. a1- Ă . т – 51. a1- , b- 52. VACS (Veterans Administration Cooperative Study) 53. a1- т 29, 54. () L- . . () () () a1- . . 55. Â 56, 57. 58 59-67. т 60-67. ʂ . (.. ) 68, 69. 70. , , , , . – , . , 68. – . 69. – – () II 71. II 72. . . 73-77. ( ) т 78. Ă 3, 24. II т 72. 79. 79-83. Ԃ . II , ; 84-86. 87. Ԃ 87. 88. Ԃ – – 89. I II . Ԃ – I ( I) in vitro – 90, 91. I- in vivo . I- , 92. . I- Ԃ 93. I- . II 94. in vivo. – 54. a– a2- 95 Ă . – . 96. a2- 97. ( ) . 1- a2- 97-99. (a– ) a2- 95. 97, 100. in vivo 1- 68. 68. ; 68. a b- ; ( ) 30, 101. 1- 102. 103-105. b- Ă . 106. . . . . -1 ; – 107, 108. ; 109. 108. G- 110. , – . , , , 28. ( ) 24, 111. – 112. – . , II CGP 48369 56. 113-115. 116. Ԃ – , , -, . , , , 117. a- 10, 118. a1- in vitro, in vivo 10, 118. Â . . – . . . (т ) – . . 3, 119, 120 т 121. т 122. – .

| | | | | . | . | |

Источник